Director Michael Winner’s melancholy noir entry quietly smolders amid an atmosphere of casual debauchery enhanced by Otto Heller’s gorgeous monochromatic cinematography. The early 1960s Ladbroke Grove setting is laden with sleazy diners, street food and junk stalls, and post-war Victorian walk-ups transformed into boarding houses occupied by wayward young men and women who casually hop into bed with each other, seeking an illusory something that might give their life meaning. Basement apartments have been transformed — with no improvements — into crowded, raucous jazz clubs, where patrons drink, dance and pair off for another night of meaningless sex. These folks don’t know it yet, but they’ll be right at home when London’s swinging ’60s erupt in the next few years. (The film’s title refers to the postal code district that includes Notting Hill and Kensington.)

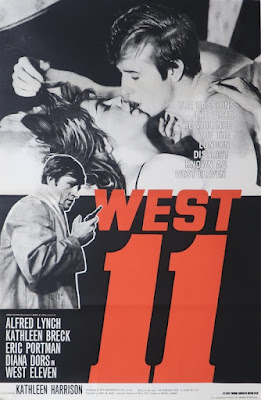

Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall’s screenplay — adapted faithfully from Laura Del-Rivo’s 1961 debut novel, The Furnished Room — focuses on Joe Beckett (Alfred Lynch). He’s a gloomy young man — he refers to himself as an “emotional leper” — who has lost his Catholic faith and works soulless jobs just long enough to cover expenses for the next couple of weeks. He invariably quits in a dissatisfied huff, remains unemployed until his meager funds run out, and then finds another unhappy position. His strongest attachment is to Ilsa (Kathleen Breck), a self-centered free spirit incapable of remaining faithful; this heightens Joe’s misery.

He comes to the attention of the older Richard Dyce (Eric Portman), an ex-military man turned con artist, who’s itching to get his hands on the wealthy inheritance promised by his elderly aunt. Not willing to wait for her to die of natural causes, Dyce concocts the “perfect” murder scheme, choosing Joe because he’s somebody with absolutely no connection to the old woman. (One wonders if Del-Rivo borrowed this idea from Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train.) Joe, desperately seeking a way to re-ignite his long-dormant emotions, recklessly accepts the assignment.

Winner’s 1963 film is laden with jazz, both diegetic and non-diegetic. Heller’s sweeping overhead pan of Ladbroke Grove opens the film; the camera then slides into one upstairs window, where Joe and Isla have sunk into a post-coital squabble. Melancholy sax introduces composer Stanley Black’s title theme, which erupts with a big band splash as the credits are superimposed over Joe’s angry stroll through the neighborhood. Clarinetist Acker Bilk introduces the theme’s core 4-3 motif: a lament repeated each time Joe reaches low ebb, as the story proceeds. (In an unusual touch, Bilk gets his own credit, for the title theme “Played by Mr. Acker Bilk.”)

The scene soon shifts to a crowded bottle party, where Joe flirts with the somewhat older Georgia (popular sex goddess Diana Dors) and then sorta-kinda makes up with Isla. People dance to phonograph records that play, among other early rock ’n’ roll hits, The Country Gentlemen’s “Baby Jean.” Dyce begins to “groom” Joe for what is to come, while also smoothly arranging to live with Georgia for awhile.

Subsequent scenes take place in Studio 51, a basement club that features trumpeter/cornetist Ken Colyer’s Band, famed at the time for its New Orleans Dixieland sound. The combo likely includes Mac Duncan (trombone), Ian Wheeler (clarinet), Johnny Bastable (banjo), Ray Foxley (piano), Ron Ward (bass) and Colin Bowden (drums). During several visits as the story proceeds, the band delivers lively readings of “Virginia Strut,” “I’m Travelling,” “La Harp Street Blues,” “Creole” and “Gettysburg March.” Drummer Tony Kinsey’s Quintet is featured at another club: Peter King (sax), Les Condon (trumpet), Gordon Beck (piano) and Kenny Napper (drums). They rattle off a ferocious handling of “What a Gas!”

Black’s score delivers a burst of cacophonous jazz when Joe, finally genuinely angry with Isla, ejects her from his apartment (not the last time this will happen). Later, at one of Joe’s many low ebbs; he watches a wrecking ball demolish a sagging structure; explosive jazz pops are heard each time the ball smashes into a wall.

An attempt to find solace with the eccentric Mr. Gash (Finlay Currie), who lives in the book-laden flat downstairs, concludes abruptly when a horrified Joe realizes that this unhappy and isolated elderly gentleman might represent his own future. He flees as Acker’s clarinet delivers a forlorn arrangement of the title theme, yielding to an equally mournful trumpet when Joe — now homeless, and with no other options — succumbs to Dyce’s proposal. In a rare moment of jubilation, Black supplies some swinging “traveling jazz” as Joe and Dyce roar off in the latter’s sports car.

An ominous cue tracks Joe when he later approaches Dyce’s aunt’s mansion via the nearby fields; the title theme’s 4-3 motif kicks in, the orchestra developing intensity and concluding with a pensive stinger when he enters her home.

Following an irony-laden climax, Bilk’s clarinet repeats the doleful title theme a final time; the music swells when Heller’s camera plans to a close-up of the vacancy sign at Joe’s former lodgings: Kildare House, 26. Cue the end credits, fade to black.

No soundtrack album was produced, although the five Colyer Band tracks have been gathered on the 1993 digital version of the 1963 LP Colyer’s Pleasure; and the Kinsey Quintet’s “What a Gas!” is included on the group’s 1961 album, An Evening with Tony Kinsey.