This was a tough call.

The story certainly is ideal; this is a brooding crime drama in the classic all-will-not-go-well mold. But “brooding” also is an apt description of the bulk of Quincy Jones’ score: far more orchestral gloom than actual jazz cues. On top of which, the minimal jazz elements are further obscured by the numerous gospel and R&B tunes that director Robert Alan Arthur seems to favor over Jones’ contributions. Reluctant as I was, to discard a Quincy Jones score, at the end of the day there simply wasn’t enough jazz to justify inclusion.

********

Time hasn’t been kind to 1969’s The Lost Man, which at this point is almost a lost movie (and an equally lost soundtrack album). The plot is a quaint relic of the late 1960s rise of Black militant groups, with star Sidney Poitier’s character displaying a level of calm nobility that seems out of place, given the era’s combustible national mood. Director Robert Alan Arthur’s script is a disguised remake of British author Frederick Laurence Green’s 1945 novel, Odd Man Out — adapted to the big screen in 1947, starring James Mason — with the then-contemporary Black militants standing in for that book’s focus on Northern Ireland’s WWII-era unrest.

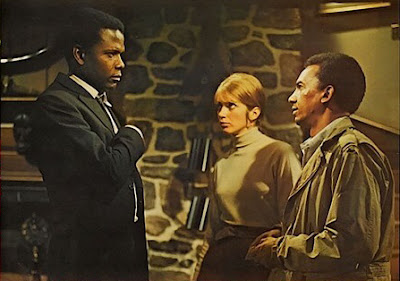

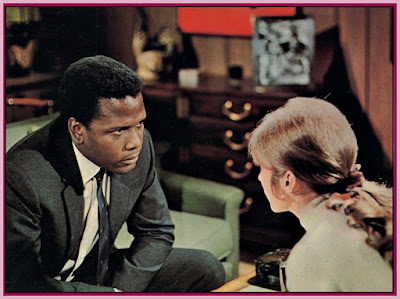

Poitier stars as Jason Higgs, a lieutenant in a well-organized — but never identified — group of Black militants operating from the slums of an average American big city. Needing funds to help the families of imprisoned group members, Higgs leads a payroll heist that goes horribly wrong; he’s wounded while fleeing with the money, and — worse yet — kills somebody in the process. Higgs’ three confederates don’t last long on the run, but he briefly stays ahead of a massive police hunt, thanks to Cathy Ellis (Joanna Shimkus), a liberal social worker who has fallen in love with him. But the net tightens quickly, leading to a bleak conclusion lifted directly from Green’s novel.

By this point in their respective careers, Poitier and composer Quincy Jones had become a highly successful team; The Lost Man was the fourth of their seven big-screen collaborations, following (among others) In the Heat of the Night, and prior to that film’s sequel, They Call Me Mister Tibbs.

Jones augmented the studio orchestra with jazz cats such as Bud Shank (reeds), Arthur Adams (guitar), Ray Brown and Carol Kaye (acoustic double bass), and Emil Richards (percussion). Given the inner city setting, and the importance that some of the characters place on church activities, Jones laced the score with numerous gospel numbers that he co-wrote with lyricists Dick Cooper and Ernie Shelby. The funk-laden title song is one such example: The film’s credits appear behind a grim montage of big-city slum life, while Jones’ catchy, percussive theme is augmented by whistles, vocal shadings and the voices of The Kids from PASLA. Their cheerful lyrics gradually are overpowered by rising horns and strings, anticipating the dangerous heist that is about to unfold.

Once the plan is set in motion, Higgs and his confederates exit their decaying tenement headquarters; Jones inserts an anticipatory cue that mimics footsteps before developing into a throbbing groove — ba-bum ... ba-bum ... ba-bum — given additional intensity with the insertion of bass, guitar and electric keyboard licks. (A variation of this tense, expectant cue repeats later, when the cops close in on two of Higgs’ associates.) The doomed heist kicks off to a similar percussive cue, which also introduces the film’s primary action theme: a tense, 2-2-2-3 horn motif backed by wicked bass licks. The cue initially sounds expectant, given Higgs’ careful planning, but the musical mood shatters as everything goes wrong. Moving forward, Jones’ occasional references to this theme reprise in slower, grimmer arrangements.

On a gentler note, Jones contributes a lovely, minor key lament — the melody taken by woodwinds, with soft piano comping — that is heard each time Higgs and Cathy share a quiet moment. Before the crime goes down, the cue’s mood is playful and exploratory, reflecting Cathy’s barely concealed wish that she and Higgs could become an item. Much later, once Higgs is on the run, Jones gives this love theme bleaker instrumentation: This final moment of intimacy will, indeed, be their last.

The various source cues include the reverential “He’ll Wash You Whiter Than Snow,” performed by a church choir that Higgs hears, in passing; and the R&B-hued “Try, Try, Try,” which emanates from a pier side restaurant/bar dubbed The Swingin’ Lighthouse. When two of Higgs’ confederates try to hide in a brothel, they party with the girls as a pair of saucy R&B tunes — “Sweet Soul Sister” and “Rap, Run It On Down” — play on a phonograph. (Alas, they’re betrayed by the brothel madam, who immediately calls the cops.)