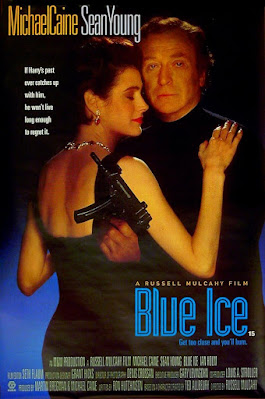

Director Russell Mulcahy’s Blue Ice (1992) doesn’t come close to that 1965 classic, but Michael Caine’s suave presence makes this modest entry reasonably palatable for undiscriminating viewers, who’ll nonetheless raise their eyebrows over the numerous contrivances in Ted Allbeury and Ron Hutchinson’s script. This is must-see viewing for our purposes, however, because the film spends considerable time in the jazz club run by Caine’s character, Harry Anders. Mulcahy devotes generous footage, half a dozen times, to the high-octane swing performed by the club’s resident septet: Gerald Presencer, trumpet; Peter King, alto sax; Steve Williamson, tenor sax; Bobby Short, pianist and vocalist; Anthony Kerr, vibes; Dave Green, bass; and Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts. Short also has a sizeable supporting role as one of Anders’ friends, Buddy.

Following a prologue that finds a guy taking photos near London’s Tower Bridge, while being watched by those inside a suspicious-looking red van, the opening credits conclude as Harry drives his posh Jaguar through London’s Piccadilly Circus region. He pops a CD into the car player, which delivers some tasty big band swing when he pauses for a red light. Stacy Mansdorf (Sean Young), driving the car behind him, is distracted by a phone call from the fellow taking pictures — former boyfriend Kyle (Todd Boyce), we later learn — and crashes gently into Harry’s car.

The damage is minimal, but Harry is nonetheless apoplectic — it’s a Jag, for God’s sake! — and he gets even angrier when she blows him off and speeds away. Harry gives chase, against a peppy jazz cue by soundtrack composer Michael Kamen, and pulls alongside when she finally parks. Harry’s fury melts (a bit of a stretch) in the face of Stacy’s coquettish nonchalance; when she suggests continuing their “conversation” over a drink, he naturally takes her to his bar (not yet open for the evening trade). They exchange come-hither glances and flirty banter while Buddy, accompanying himself on solo piano, croons the Ian Grant/Lionel Rand classic “Let There Be Love,” made famous by Nat King Cole.

Stacy hangs around long enough to enjoy a double-time sizzler by the club septet, and over the next few days becomes a frequent presence at Harry’s side. The affair turns serious when he takes her to his apartment, above the bar; he cooks an elaborate dinner while soft quartet jazz emanates from his stereo system. Alas, the meal remains uneaten when they make love for the first time; Kamen backs this with a soft, sexy sax cue. Subsequently learning that Stacy is married to the American ambassador to England raises Harry’s eyebrows, but doesn’t interfere with the affair. (That said, we viewers wonder what else she’s concealing, and why the hell Harry is being so dense.)

Turns out Stacy has “a problem” — what a surprise! — and needs a favor. Former boyfriend Kyle has some “indelicate letters” that she’d like retrieved, lest their public exposure embarrass her husband … and she has no idea where Kyle is. Harry, retired from MI6, cheerfully agrees to track him down. He and longtime cop buddy Osgood (Alun Armstrong) confer in the club one evening — against more swinging sounds from the resident septet — and, soon enough, Osgood locates the guy. Alas, Harry shows up and finds Kyle and Osgood dead; worse yet, Kyle is revealed as an undercover cop, and Harry is arrested for both murders. He has unwittingly stepped into a hornet’s nest that involves dire doings by either clandestine American agents or bent MI6 operatives; he can’t tell which. Stacy pulls strings and gets Harry freed from jail; he returns to his club, flummoxed, to find Buddy accompanying himself on a soulful reading of Ted Koehler and Rube Bloom’s “Don’t Worry ’Bout Me” (a 1938 classic covered by everybody from Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, to Frank Sinatra and Joni Mitchell).

Feeling the need for higher-level assistance, Harry looks up former MI6 buddy Sam Garcia (Bob Hoskins), now working as a security consultant for upper-echelon aristocrats and government officials. Poor Sam doesn’t last long, and is executed while Harry is drugged and tortured for information by a mid-level MI6 operative — Jack Shepherd, as Stevens — during a weirdly overcooked, laughably disorienting sequence set to discordant free jazz. Trouble is, Harry genuinely doesn’t know anything … at least, not yet. His rage, upon learning of Sam’s murder, goes into hyperdrive when summoned for a dressing-down by condescending former boss Sir Hector (Ian Holm), who orders Harry to “drop it.” (Like hell.)

Revelation comes when Stacy finally shares the information Kyle gave her, during the phone call that prompted her to rear-end Harry’s Jag. (Like, what has she been waiting for???) Another sensual sax cue backs their lusty round of shower sex, after which we race into a truly ridiculous climax amid the hundreds of stacked containers awaiting shipment from the Port of London Authority, along the River Thames. The true villain is revealed, to nobody’s surprise.

Final scenes include a visit to the hospital, where Buddy is recuperating from his wounds. (Did I neglect to mention that Harry’s club was bombed?) Harry and Stacy find him serenading fellow patients on the ward piano, while singing another torch standard: Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer’s “This Time the Dream’s On Me.” Alas, Stacy’s husband has been recalled to the States, so they part in the manner Harry promised, back when their affair began: toasting each other with champagne, against a mournful sax cue.

Bobby Short gets one more solo, during the first half of the lengthy end credits: Brooks Bowman’s “East of the Sun (and West of the Moon).” The club septet roars through a final blast of jump jazz during the credits’ concluding half.

Mulcahy insisted otherwise, during a 2016 interview, when asked if Caine’s Harry Palmer films had influenced Blue Ice. He was being disingenuous; Allbeury and Hutchinson’s script feels like a Palmer thriller in all but name. Both Palmer and Anders are jazz fans and accomplished cooks, and are insolent in the face of authority. Both ultimately are betrayed by an MI6 superior. Most tellingly, this film’s interrogation sequence strongly evokes a near-identical bit of torture in The Ipcress File.

No soundtrack album was produced, although a couple of the Peter King originals performed by the club septet — “One for Sir Bernard” and “Blues for S.J.” — can be found on his albums. Charlie Parker’s “Perdido” and the Pete Thomas Quintet’s “Blue Bop” also are covered by the septet.