The television component of my two-volume series focuses on shows that successfully landed on network schedules … if only for a month or two, in some cases. With one exception, I didn’t even try to delve into unsold and/or unaired pilots that never made it to series. (I did briefly cite writer/director Blake Edwards’ failed 1954 attempt to turn Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer into a series, with Brian Keith in the starring role.)

Entire books have been written about such unsuccessful efforts, most notably Lee Goldberg’s 828-page Unsold Television Pilots: 1955-1989 and Vincent Terrace’s Encyclopedia of Unaired Television Pilots, 1945-2018. The latter — also published by McFarland — boasts a heart-stopping 2,923 entries.

All this said, a few have come to my attention during the past couple of years: well within my books’ brief, in terms of genre and jazz scoring.

The best of these — in terms of music — is Take Five, a 1957 pilot that aired on March 22, 1958, as the 18th episode of the fourth and final season of the anthology series Heinz Studio 57. It came to my attention thanks to fleeting mention in Jon Burlingame’s recently published Music for Prime Time (which readers of this blog should rush out and purchase).

The show features a terrific jazz score by Elmer Bernstein, very much like his work for the big screen’s Man with the Golden Arm and Sweet Smell of Success. If the episode’s IMDB entry can be taken as gospel, Bernstein’s studio band is stunning: Pete Candoli and Manny Stevens, trumpet; Milt Bernhart, trombone; Ted Nash, alto sax; Dave Pell and Champ Webb, tenor sax; Arthur Gleghorn, flute; Red Mitchell, bass; Shelly Manne, drums; and — wait for it — Johnny Williams, piano.

Dennis O’Keefe stars as Dick Richards, ostensibly the editor of a respected jazz magazine titled Take Five, but — unbeknownst to all but his cop buddy Pete Lonigan (Bart Burns) — also an “undercover man” for the district attorney’s office. (Bear in mind, this show was made two years before that title became synonymous with the Paul Desmond classic debuted by Dave Brubeck’s Quartet.)

As O’Keefe explains during lengthy, private eye-style voiceovers, Richards haunts New York’s club district after hours, because “the best music is made at night.” He has taken a personal interest in young singer Jen Bradley (Bethel Leslie), about to debut this particular evening at a posh club named for its owner, Monte (Nestor Paiva). Alas, Jen has fallen in love with Hap Gordon (Mike Connors), a slick-talking skunk with a serious gambling problem. When Jen refuses his plea for a “loan,” police subsequently find his car abandoned by a pier, with a suicide note inside. Jen collapses, believing his death to be her fault.

Ah, but it feels too convenient to Richards, who deduces that Hap’s so-called suicide is merely a ploy to get gangsters off his back.

It subsequently becomes a very busy night. In the space of what can’t be more than a few hours, Jen rebuffs Hap; police find his car and suicide note; Jen has a nervous breakdown, requiring a doctor; Richards starts asking around, trying to find somebody who might know where Hap would hide; the increasingly distraught Jen tries to slash her wrists; Richards finally gets a solid lead and finds Hap in an apartment with equally clueless second girlfriend Myra (Vivi Janiss), and drags him back to show Jen what a true louse he is … and she somehow composes herself and still hits the stage, on schedule, to briefly croon Louis Armstrong’s “I Got a Right to Sing the Blues.” To thunderous applause, of course. (Whew!)

Bernstein’s energetic title theme repeats a 6-5 motif on unison horns, with sparkling 1-1-1-3 brass counterpoints, all backed by rumbling percussion and a propulsive beat. Richards’ opening voice-over is heard over a cool, gently swinging cue; much later, when he shadows Myra as she hails a cab en route to joining Hap, her movements are shadowed by a saucy piano and drum riff.

Alas, director James Nelson lacks imagination; he relies far too heavily on tight close-ups that do his actors no favors. Set design is minimal; everything has the feel of a hasty shoot on a back lot. (The atmosphere of better shows, such as Peter Gunn, is wholly missing.) The bare-bones script is padded by an early evening visit to Club 25, where Richards watches as special guest star Dennis Day sings Nat King Cole’s “Almost Like Being in Love” (a sequence that seems to run forever). It’s easy to see why this pilot didn’t sell.

Even so, it has survived to this day, and can be found by the diligent and curious.

Regardless of the pilot’s failure, Bernstein obviously thought highly of his title cue; he included it on his 1962 album, Movie and TV Themes. This longer version adds generous solos on sax, bawdy brass and muted trumpet, all against a finger-snapping vamp.

A portion of this pilot can be viewed here.

********

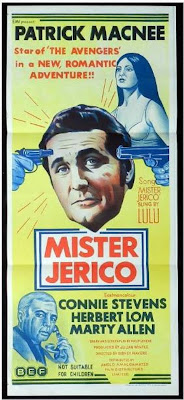

Next up is Mr. Jerico, a 1969 telefilm in which Patrick Macnee starred, immediately following his work on the final season of The Avengers (alongside Linda Thorson’s Tara King). This potential series pilot, made for the UK’s Lew Grade — but ultimately “burned off” in the States as an ABC Movie of the Week entry on March 3, 1970 — re-united Macnee and much of the Avengers team: producer Julian Wintle, director Sidney Hayers, scripter Philip Levene, cinematographer Alan Hume, editor Lionel Selwyn and — most crucially, for our purposes — composer Laurie Johnson.

On a lesser — but still familiar — note, this film’s title credits font is identical to that of The Avengers.

Macnee stars as veteran con artist Dudley Jerico, introduced during a prologue as he fleeces a wealthy mark with the ol’ “I found your wife’s priceless bracelet” swindle. Once safely away, he and partner Wally (Marty Allen) fly to Malta — where much of this film was shot — and set up shop at the island’s Phoenicia Hotel. The plan: to trick wealthy Victor Rosso (Herbert Lom) out of $500,000 by claiming to have the long-believed-lost second Gemini Diamond, to match the one Rosso already possesses.

Jerico and Rosso are wary associates; Jerico has “scruples,” whereas the ruthless millionaire has none. Rosso is assisted by secretary Susan (Connie Stevens) and taciturn thug Angelo (Leonardo Pieroni), the latter handling sidebar assignments such as kidnapping at gunpoint. Russo’s gem is protected by an elaborate security system, the details of which — in the manner of all egotistical villains — he cheerfully shares with Jerico. Our hero returns later that evening, easily evades the security measures, and switches the Gemini for a paste replica, intending to then trade the actual, supposed “second” gem for the half-million.

What initially seems far too simple quickly gets complicated, when it turns out that Jerico has snatched another paste replica. Further hijinks ensue with the arrival of Claudine, a shady French aristocrat who also claims to have the second Gemini. Despite subsequently exchanging lusty kisses with both Susan and Claudine — Jerico genuinely likes the former, and merely strings the latter along — he fails to realize what we viewers immediately see: Stevens is playing both women. (Seriously? Discard Susan’s prim glasses, add a wig, a French accent and a bikini, and Jerico can’t tell he’s smooching the same dame?)

That aside, the double, triple and quadruple switcheroos become amusing, with everything building to a satisfying conclusion.

Alas, the acting is wildly uneven. Macnee is his usual charming self, and Stevens does well in the dual roles. But Lom is a joke villain who too frequently looks and sounds like his Inspector Dreyfuss character in the Pink Panther series, and Marty Allen is beyond embarrassing. His character does little but read girlie magazines and leer at women … and this film supplies plenty of bikini-clad eye candy. Even by late 1960s standards, the sexism is wincing.

The location work notwithstanding, plenty of expense was spared elsewhere. Far too much time is spent in lackluster hotel rooms — I’m sure the actual Phoenicia is far better appointed — and all driving scenes involve glaringly poor rear projection work.

Ah, but Johnson’s wall-to-wall score is a lot of fun: very much in the mold of the jazz/pop action touch that made The Avengers’ music so memorable. Highlights include the dynamic jazz cue that backs a speedboat chase during the prologue; cool vibes work on a suspense cue, as Jerico gets away with what he believes is the actual Gemini; some up-tempo jazz when “Claudine” is dropped off late one night, and then pursued by Jerico; some nifty “traveling jazz” when Jerico chases after Susan’s car; and a terrific action vamp when our heroes successfully escape from Rosso … albeit not with the massive haul they expected.

Johnson apparently didn’t think much of this assignment. It doesn’t warrant a mention in his 2003 memoir, Noises in the Head; nor are any cues included in his three-volume, nine-CD box sets of 50 Years of The Music of Laurie Johnson. This likely results, in part, from the fact that while Johnson contributed the entire underscore, the title theme came from Beatles stalwart George Martin and composer Don Black, with the vocal by Lulu. Even her lusty delivery can’t save the song’s inane lyrics; it’s hard to imagine that Black could sink so low.

I’m sure nobody was surprised when a TV series failed to materialize. The curious can watch it here.

********

The original Hawaii Five-O ran an impressive 12 seasons, from September 1968 until April 1980. The 2010 re-boot did almost as well, running 10 seasons through April 2020.

Few people realize that CBS attempted an earlier re-boot; producer Stephen J. Cannell was hired to oversee an effort that got as far as a never-aired 1997 pilot episode.

James MacArthur — “Danno” in the original series — has become governor of Hawaii; the film begins when he’s critically wounded during an assassination attempt that kills current Five-O head Alex Bowland. The case falls to his second-in-command, Jimmy Xavier Berk (Gary Busey) and import Nick Wong (Russell Wong), on leave from his mainland FBI duties. The various Five-O squad members shun Nick, feeling that he “betrayed” his Hawaiian origins by taking that mainland job.

It’s easy to see why the pilot failed to sell. Although Busey’s Jimmy is affable enough, in the laid-back Thomas Magnum mold — this is a Cannell show, after all — Wong badly overplays Nick’s tight-assed, “operational, by-the-book BS.” Cannell’s hilariously overcooked script initially suggests that island crime boss Napoleon DeCastro (Branscombe Richmond) ordered the hit, but it turns out he was framed by Russian mob boss Col. Yodin (Achilles Gacis) and his femme fatale ex-KGB killer, Oksana Demetrios (Natasha Pavlovich).

Jimmy and Nick’s prickly mutual antipathy isn’t the slightest bit credible, their final-act kumbaya moment even less so. Fellow Five-O investigators played by Steven Flynn and Elsie Sniffen are under-used to the point of being anonymous.

While it’s nice to see former Five-O members Chin Ho Kelly (Kam Fong), Kono Kalakaua (Zulu) and Truck Kealoha (Moe Keale) on hand to provide “old-timer support,” the former represents a glaring continuity error … given that Chin Ho was killed in the final episode of the original series’ 10th season (!).

The sole surviving print has no end credits, so we can’t be absolutely certain who scored this pilot; that said, the many suspense and action cues sound very much like what Mike Post and Pete Carpenter (who died in 1987) delivered for The Rockford Files and Magnum, P.I. Given that Post and Cannell maintained a long-term partnership for several decades, it’s a safe bet that Post also handled this assignment. His taut, slightly revved-up 50-second arrangement of Morton Stevens’ iconic title theme boasts more electric guitar and bass, which add even additional sizzle against a similar smash-cut montage of Hawaiian scenery and pulchritude. The underscore’s best moment is a sassy suspense cue when DeCastro is freed from jail, so that his car can be tailed by Five-O watchdogs.

The pilot can be viewed here, complete with occasional time codes.

No comments:

Post a Comment